Giacomo Puccini did not have to wait long to enjoy the last laugh regarding the great trio of operas he composed at the turn of the 20th century: La bohème (1896), Tosca (1900), and Madame Butterfly (1904). None of his three earlier ones, or the seven later, achieved the enormous success they did, although acclaim was not immediate, and Puccini made revisions to strengthen their impact.

Music and Artistic Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra. Photo: Jeff Fusco

Critics had mixed reactions when Arturo Toscanini conducted the 1896 premiere of La bohème in Turin and things did not improve at the initial performances in England and America. The leading New York critic began his review of the Metropolitan Opera premiere in 1900: “La bohème is foul in subject, and fulminant but futile in its music.” The fate of the opera turned quickly and Bohème has only been absent from the MET nine seasons since then, logging over 500 performances and being the most-often presented work in the company’s history.

And now Philadelphia Orchestra audiences have the chance to hear La bohème performed in concert, following the success of Tosca six seasons ago. Such a presentation allows us to focus on Puccini’s music and appreciate how much of the drama, sight unseen, is manifested in the score itself. Listeners are invited to stage the work in their own minds.

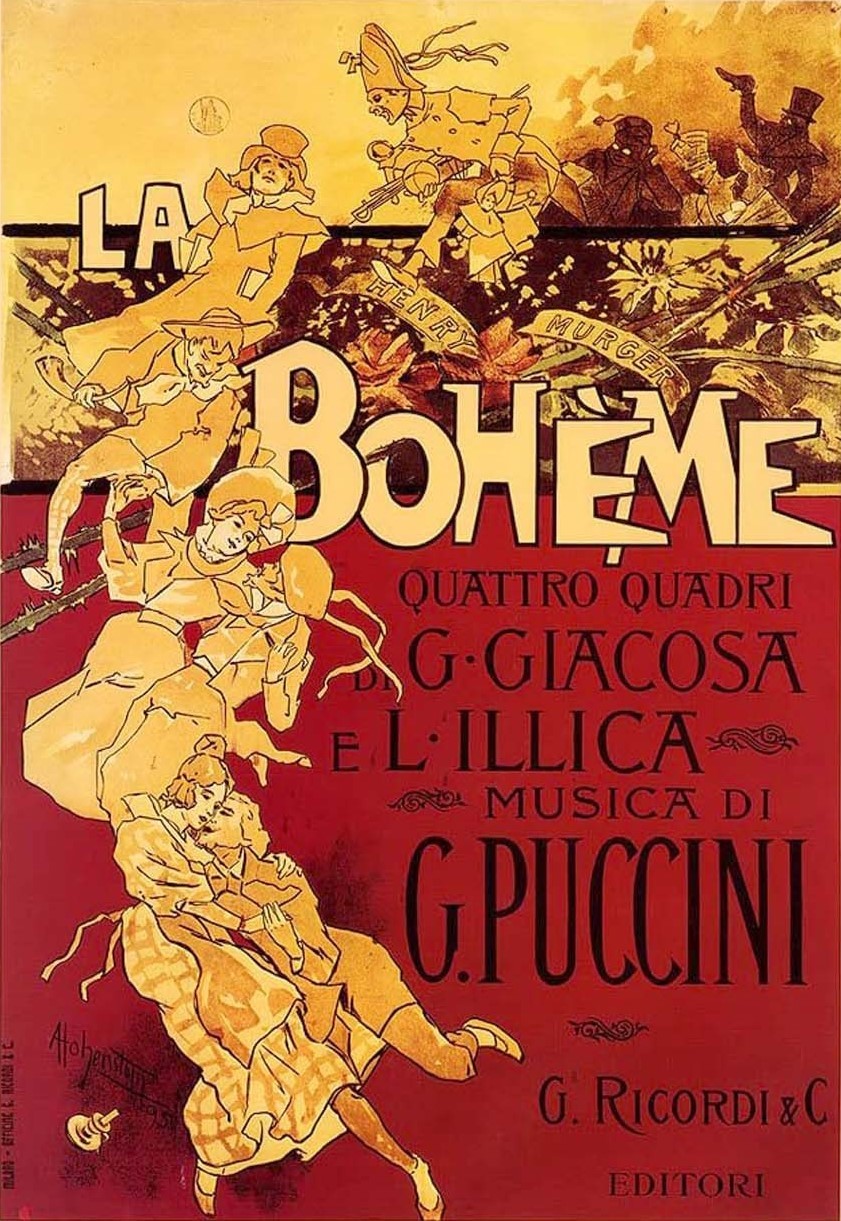

Poster for the 1896 premiere of La bohème at the Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy

La bohème may now seem so familiar, popular, and beloved that the initial controversy is surprising, making it instructive to consider what caused some antagonism. While most critics may not have found Bohème “foul,” many thought it trivial. The stories of most operas during the genre’s first three centuries—from Monteverdi through Verdi—usually dealt with elevated circumstances drawn from the Bible, classical antiquity, historical events, Shakespeare, and so forth. Comic characters and scenes were sometimes inserted into tragedies, but not freely merged, and the pure comic delights found in Rossini were judged by different standards.

It may be easy now to dismiss Bohème as sentimental—a soap opera—but it was very much of its time at the volatile turn of the century. The most recent fashion in Italian opera was verismo—“truthism”—that aimed to capture real life and lived experience, often of the poor. Two of the earliest hits remain well known: Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana (Rustic Chivalry, 1890) and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci (Clowns, 1892), which are often performed together as a double bill affectionately known as Cav/Pag. They depict everyday life in poor Southern Italy, which from the perspective of the affluent North in many respects seemed just as distantly exotic as Asia or America, where Puccini also set successful operas. Both operas end, as many verismo ones do, with grisly murders.

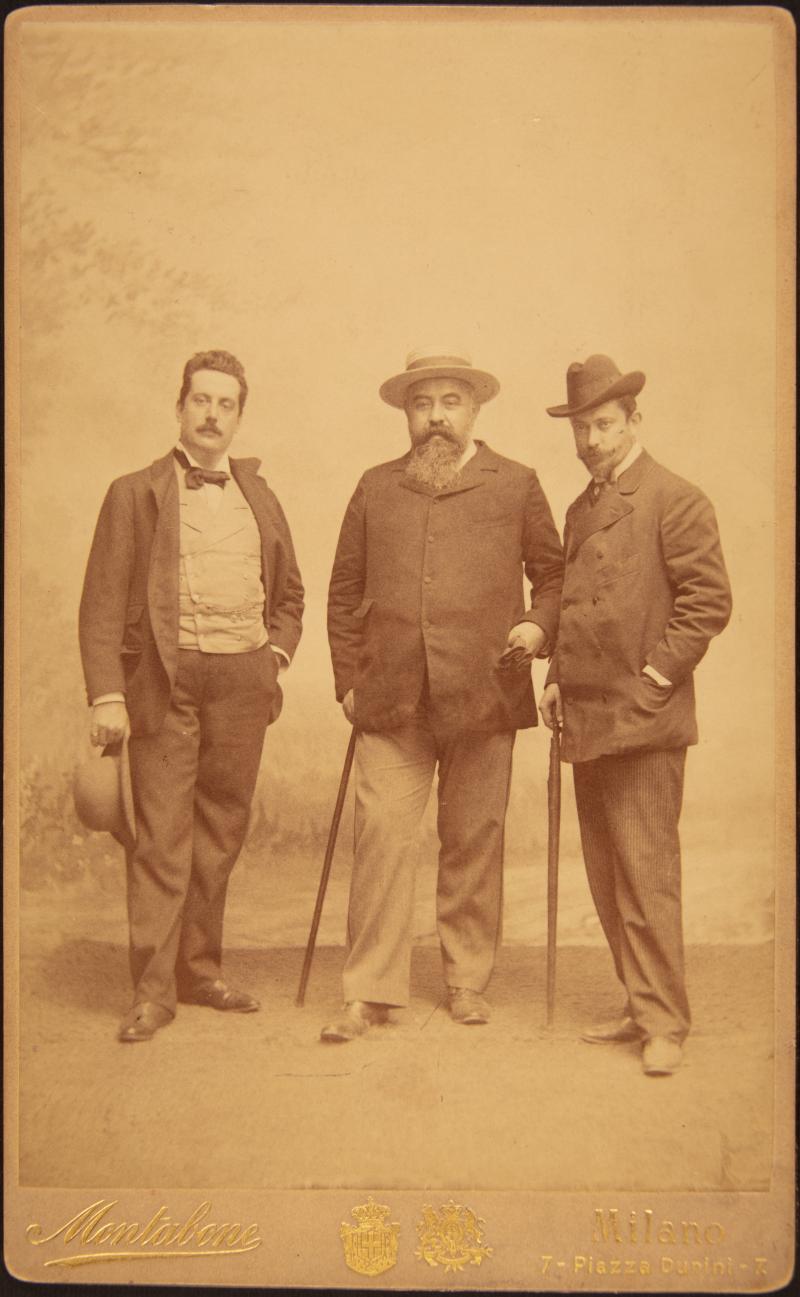

(L to r): Giacomo Puccini with Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, the librettists for La bohème, in 1896

Setting La bohème in the Paris of the 1830s might not seem terribly exotic, but Puccini was nonetheless doing new things with realism. The opera depicts the everyday lives of a fun-loving group of struggling artists, the consumptive seamstress Mimì, and their circle of friends. There is the poet Rodolfo (the tenor lead), the painter Marcello (constantly quarrelling with his lover, Musetta), the philosopher Colline, and musician Schaunard. It may not be entirely fanciful to compare much of the opera’s first two acts to present-day situation comedies on TV, inevitably bringing Friends to mind. But the romanticized poverty, good-natured banter, and high jinks of the Bohemian gang turn tragic as Mimì’s health declines and her romance with Rodolfo is doomed.

The literary sources Puccini used for the story also point to sitcoms as he based the opera on a newspaper series. In 1845 the French writer Henry Murger started publishing stories in Le Corsaire called Scènes de la vie de bohème (Scenes of Bohemian Life). They proved extremely popular, so much so that he collaborated with Théodore Barrière to turn them into a play, which premiered in Paris in 1849. This too was an enormous hit. The night of the premiere, a publisher acquired the rights to turn the series into a novel, which made Murger rich.

Four decades later, Puccini became attracted to Murger’s stories and started the Bohème project. At a very early stage, in March 1893, there was some very public controversy as both Puccini and Leoncavallo announced they were adapting Murger’s book. Puccini welcomed the competition and declared in a prominent newspaper: “Let the public judge.” Leoncavallo’s version premiered in 1897, a little more than a year after Puccini’s, and initially proved more successful. Although already in his mid-30s, Puccini was still near the beginning of a glittering career. After a somewhat rocky start with Le Villi (1883) and Edgar (1889), he scored his first success in 1893 with Manon Lescaut.

Original set design for Act II of La bohème by Adolf Hohenstein

Puccini’s enterprising publisher, the formidable Giulio Ricordi, assembled the creative team for La bohème. To test the waters, he first enlisted librettists Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, both successful playwrights, to polish revisions of Manon. Having passed this trial, they started work on Bohème and would later write Tosca and Butterfly. It took them more than three years to craft the libretto, in part because Puccini was so demanding, constantly asking for revisions and for revisions of revisions. They nearly gave up, but Ricordi used his considerable diplomatic skills to keep the project on track. In the end Giacosa admitted the composer’s determination was worth it: “Puccini has surpassed all my expectations, and I now understand the reason for his tyranny over verses and accents.”

The opera departs in crucial ways from the book (and even more from the play). Mimì is depicted as a more fragile figure, less of a gold digger, which makes her fate particularly touching. Puccini created many memorable heroines, usually more interesting than their lovers, and specialized in two contrasting types—the strong and the fragile. Tosca and Turandot exemplify the former, but Puccini more often depicted the vulnerable and doomed, including Mimì, Butterfly, and the enslaved Liù in Turandot—“Great sorrows in little souls,” as he once put it. This was all happening at a crucial moment for women in society, an issue that proved fertile for artistic exploration.

Original costume design for Mimì in Act I of La bohème by Adolf Hohenstein

There is arguably another kind of realism at work in Bohème, one quite similar to the background of Verdi’s La traviata, an inspiring work for Puccini. Part of the enduring power of both operas is that their literary sources are closely connected to the lives of their authors, Henry Murger and Alexandre Dumas fils, as well as to those of the composers. Murger struggled in Paris early in his writing career and Puccini’s time as a student at the Milan Conservatory was likewise challenging. They all seem to have identified personally with the situations they depicted in words and music. This mitigates the sentimentality because the “real” experiences depicted on stage resonated with the literary and musical creators, offering a more subtle layer of “truth.”

An observation by the eminent literary critic George Steiner applies to La bohème. He contrasts what he calls “masters of the absolute,” such as Aeschylus and Wagner, with how Shakespeare and Verdi take account of the way life really works, knowing “that the instant in which Agamemnon is murdered [in Aeschylus’s Oresteia] is also that in which a birthday party is being celebrated next door.” And so we find ourselves in La bohème on Christmas Eve in a Paris garret and at the frolicking Café Momus as friends juggle pleasure and love with the grim realities of poverty and illness. “Oh, beautiful age of deceits and utopias,” says the painter Marcello, “one believes, hopes, and all seems beautiful.”

Christopher H. Gibbs is James H. Ottaway Jr. Professor of Music at Bard College and has been the program annotator for The Philadelphia Orchestra since 2000. He is the author of books on Schubert and Liszt, and the co-author, with Richard Taruskin, of The Oxford History of Western Music, College Edition.